William Faulkner wrote, and President Obama reminded us, the past isn’t dead; it isn’t even past.

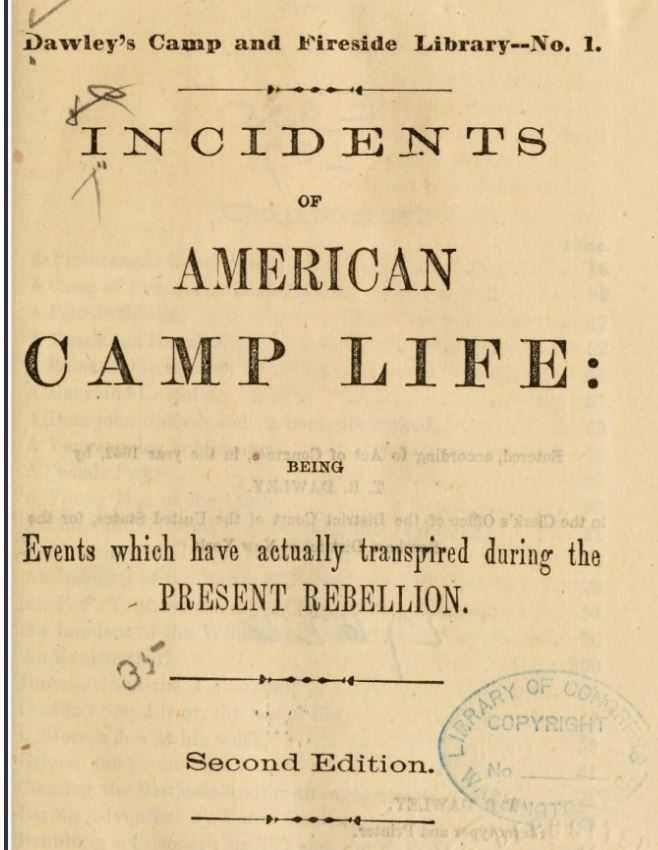

Historical fiction used to be my guilty pleasure. I’m sure when I was young I thought of it as all the things I wasn’t supposed to be embracing as a future adult: escapism, a quick, enjoyable cheat-sheet for history, and a much more fun way of learning based on storytelling rather than schooling. Maybe that’s why it’s become so popular today. Those who love historical fiction tell me it’s because they like learning something new while being entertained, and I think it’s also the thrill of living vicariously in a different time, with a chance to let your imagination loose while being safely tethered in a past reality.

Writing historical fiction offers the same delights as reading it, but magnified many times over. The author spends months and years researching the hidden by-ways as well as the exposed highways joining her characters’ lives. Much of what we learn never even makes it into the book, but it does bring us much closer to the thrill of living in a different period and place with the people created from our evolving imagination. The author becomes somewhat of an expert, completely immersed up close as if the time-travel had actually happened.

There are a number of intriguing ways historical fiction can be structured. My two current novels, Certain Liberties and The Gilded Cage take the straightforward approach, their narratives unfolding linearly as if we’re traveling along simultaneously with them. For the most part, that’s exactly the way their stories unfolded in my own mind, and it’s most certainly the method publishers are happiest with. There’s no question it’s the easiest way to follow the characters and most likely to keep all readers fully attached. It also allows the reader to make the associations and connections between then and now on his or her own (or not at all if they’re not so inclined).

However, my third novel, written but not yet edited, brings two time-periods together in the same book, and while it currently rests on my home office shelf, I’ve started studying the different ways that apposition can be presented in some wonderful novels I’m reading now. Unsheltered, by Barbara Kingsolver, has movement back and forth in time, juxtaposing one era when society faced radical change with the challenges of our own current period. The change is specifically announced by chapter title and date.

The Guest Book, by Sarah Blake, is a portrait of three family generations and the myths and secrets that make them who they were and who they become. Movement isn’t clearly marked and the reader must follow by name and description. The book uses letters, journals and personal items to cue the reader, and while often confusing at first, one gets more familiar with the characters and their lives as the narrative unfolds. It takes work but it’s worth every ounce of effort a reader puts in. Thank heaven the modern authors and their editors have some faith in us.

What The Wind Knows, by Amy Harmon, is another book with some jumping around in juxtaposed times, with similar challenges in different centuries and often very different cultures. But the association is all done by the same person. This one uses journaling from the past entirely, but the readers have to be willing to suspend their disbelief that one person could live in two different places at once. That could stop some people cold, while others remain intrigued. It’s a bold experiment but I think it works.

The Bee Keeper’s Promise, by Fiona Valpy, uses specific names and dates on chapter headings to denote changes in time, with the structure of a story told in one era about the other. It’s probably the least discreet way to move around, but one of the most clear. I have to admit I found that device a little clunky and felt it was a bit of a cop-out. We all know what it’s like to come across a historical reminder that starts us thinking and imagining, and I prefer a narrative that tries to be true to that kind of natural storytelling. And that goes for the smaller moves in time back and forth in the same century identified by years on chapter headings. Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens uses that structure, and I find it similarly artificial, as well as superficial. Or to put it another way, I think we can do better.

Many of the most experienced editors of the past preferred a linear progression they felt was easier for a reader to follow—easy reading meant increased sales and more fast money for the publisher. However, I’ve noticed the modern historical novelists often hop around like critters in the forest trying to outrun a predator. They aren’t easy on the reader at all, but some are clearer than others, and all seem to get more accessible as the reader moves on in the story. They’ve given me the courage to do some jumping of my own in the future. That’s what art’s all about: the audacity to ask questions without answers.

I now see historical fiction as a far cry from guilty pleasure. It seems to me it’s an imperative for exposing the truth. Sarah Blake, author of one of my favorite reads The Guest Book, put it particularly well in a presentation for PBS Newshour, June 19th- ‘In my humble opinion’. She said: “But what if, this time, we look at the truth in the mirror, and break now from then, making a truer now, one that doesn’t forget the past, but confronts, acknowledges, reconstructs and so, we can hope, repairs?”

Many thanks, always, to my loyal readers, breaking now from then and looking at them both in the mirror with me.

Your friend, the Unblocked! Writer

Relative. Found this particularly interesting and believe history needs to make a connection with modern reader and thus relevant and thus need for insightful character study that fictionalized provides

Thanks for rocking my brain

You understand that because you live for the past, as many do. But those who don’t are oblivious to the truths about their own identities they could find there. Yes, everything’s relative, and that relational connection is what history provides.